The Three Acts of the Penitent for Confession

Adapted from the Book, Overcoming the Evil Within: The Reality of Sin and the Transforming Power of God’s Grace and Mercy, by Fr. Wade L.J. Menezes, CPM, EWTN Publishing, ©2020 [Second Edition ©2022], p. 78-80. Available from EWTNRC.com.

+ + + + + + +

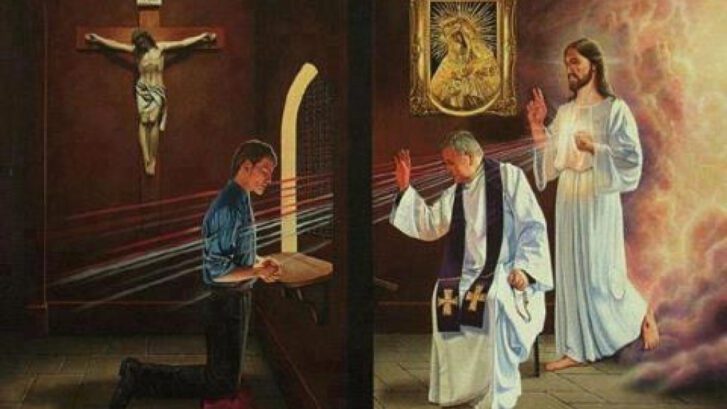

For the penitent, there are four aspects of a proper Confession: the examination of conscience, followed by what are traditionally known as the three acts of the penitent. Regarding the examination of conscience, all seven Sacraments require some kind of remote or proximate preparation before they can be received. For the Sacrament of Penance, that proximate preparation is the examination of conscience (see CCC 1454). As each Sacrament is truly a meeting with the Lord Jesus, we must ready ourselves for that meeting — in the case of Confession, by looking deeply and honestly at our lives so that we come to God with as full an understanding of the state of our souls as possible and ask for pardon.

St. Augustine, in discussing the sin of King David with Bathsheba, relates that asking for pardon for sin is tied to intellectual acknowledgement of sin: “ ‘I acknowledge my transgression,’ says David. If I admit my fault, then You will pardon it. Let us never assume that if we live good lives we will be without sin: our lives should be praised only when we continue to beg for pardon.”[1]

The three acts of the penitent, then, are contrition, confession, and satisfaction. First, regarding contrition, a distinction needs to be made between perfect contrition and imperfect contrition (also called attrition). Perfect contrition is when you are sorry for your sins most of all because they have offended God, Who is all good and deserving of all your love (as one version of the Act of Contrition states). But if you are sorry for your sins and detest them only for human motives — for example, because you dread the loss of Heaven and the pains of Hell, or because you’ve been asked to be a Godparent and the rules require you to be in good standing with the Church — this would be imperfect contrition (attrition). The great news, however, is that Holy Mother Church considers imperfect contrition (that is, a fear of divine justice, even if mixed with human motives) to be a sufficient basis for sorrow for the Sacrament of Confession (see CCC 1451–1453). St. Peter Damien explains this distinction well: “Where there is justice as well as fear, adversity will surely test the spirit. But it is not the torment of a slave. Rather, it is the discipline of a child by its parent.”[2]

Second, of course, we have to confess our sins. Confession of one’s sins should be done in a simple, concise manner; that is, maintaining the integrity of the confession, yet without going into great and graphic detail about each sin. The following important points were discussed in our first chapter, but because they are so important to making a good, worthy, and reverent confession, they’re worth mentioning again here. Mortal sins must be confessed in their kind and approximate number. Any aggravating circumstances that make a mortal sin objectively graver should be included but still mentioned simply — again, without a lot of great or graphic detail.

Remember that venial sins, unlike mortal sins, can be forgiven outside the Sacrament of Confession — by praying a fervent Act of Contrition or by receiving Holy Communion devoutly. Recall that, regarding Confession and forgiveness, God is always our Primary Mover, whether or not we are in a state of grace. When we go to Confession or make an Act of Contrition, we are responding to this movement of God’s grace in our hearts. Remember: Confessing venial sins, though not required, is strongly recommended by Holy Mother Church because it helps us fight against evil tendencies and form our consciences properly. “Deliberate and unrepented venial sin disposes us little by little to commit mortal sin” (CCC 1863). God’s sanctifying grace comes through the Sacraments, so if we do bring our venial sins to Confession, we can be certain that grace is increased in us.

The third and final act of the penitent that leads to a complete and integral confession is satisfaction, or the proper completion of the assigned penance given to the penitent by the confessor. Now, keep in mind that the penitent does have the right, if the priest gives a penance that is simply not realistic for his or her state in life — say, a homeschooling mother of seven is told to give several hours of service each week to a soup kitchen — to ask respectfully for an alternative penance. At the same time, the priest has a right to give a penance that is commensurate with the gravity of the sins confessed: In fact, he’s duty bound to do that. In most cases, the confessor will give a reasonable and specific penance so that the penitent can be assured that he or she has satisfied it fully.

[1] Sermo 19, 2–3: CCL 41, 252–254.

[2] From a letter by St. Peter Damien, bishop, bk. 8, 6: PL 144, 473–476.