“This was the problem with hanging out with vampires you got used to them. They started messing up the way you saw the world. They started feeling like friends.” Jacob (BD284)*

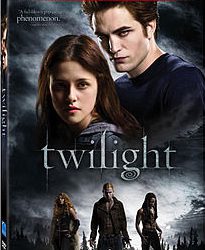

Once upon a time, vampires were bad. Remember Dracula Bram Stoker painted the Count as a blood-guzzling, preternatural monster, the implacable enemy of mankind, breathing out a disgusting odor of death, and driven by a maniacal hatred of God and of everything holy. Today, Edward Cullen, the 108 year old teenage vampire of the Twilight** novels, is represented by Stephenie Meyer as the perfect lover and the powerful protector of his beloved Bella; he is lavishly endowed with godlike gifts, he’s fabulously handsome, a cultured gentleman, a paragon of self-control, an altruist, an artist, an old-fashioned moralist an ecowarrior, even. Dracula is the horrifying villain of Stoker’s story; Edward is the lovable hero of Twilight. What’s going on?

Our values have been flipped. Vampires are now heroes dragons, too, and demons, the damned, werewolves, zombies, sorcerers, witches, cannibals, serial killers, psychopaths. These are the new heroes (sometimes antiheroes) of our books, movies, and TV shows; they’re the ones with whom we’re meant to sympathize. Do you think maybe there’s a little more wrong in America than merely another dip in our decadent tastes? Something worse going on than kicks gettin’ harder to find? Something perhaps much sicker? When Stephenie Meyer, author of the Twilight vampire romances, was recently accused of misogyny by critics (whether because of the horrors to which the writer subjected her heroine Bella or because of the moral and psychological horror that Bella herself is portrayed to be, I don’t know), Meyer quipped, “I am not anti-female, I am anti-human.” Meant apparently to be taken as sarcasm, Meyer’s reply seems to me, after a careful reading of the novels, to be a plain statement of the bias that pervades her fiction.

Here’s some of what’s wrong with Meyer’s saga.

The Monsters Are the Good Guys.

The Cullens, a coven of vampires, are portrayed as saints (Carlisle, Esme), geniuses (Carlisle, Edward), nearly perfect people. Even their faults are admirable Emmet, too strong; Carlisle, too compassionate; Jasper, too passionate; Edward, too protective; even hostile Rosalie, too motherly. Meyer (Bella Swan, that is : most of the saga is told in the first person singular by the young heroine) constantly refers to these vampires as angelic, godlike, seraphic, divine. Bella chooses Edward, her “perpetual savior (T166),” to be not just her hero, but her personal god.

[“Her grades have actually improved . . . ”]

* Reference : T -Twilight, NM – New Moon, E – Eclipse, BD – Breaking Dawn; followed by page number. ** The title Twilight is used to refer both to the novel (first in a series of four) and to the entire saga.

Do It to Death.

Bella is a self-destructive addict. Though mostly in denial, Bella is sometimes aware of her addiction owning it, even reveling in it, celebrating it. Nice guys are safe, Bella notes, therefore, to her, uninteresting (NM114). She boasts, “I wanted to be stupid and reckless, and I wanted to break promises. Why stop at one? (NM127).” First, she becomes addicted to Edward; then, when he leaves her, she becomes obsessed with risk-taking, danger, seeking to harm herself, and flirting with suicide. If a little is good, too much is excellent : that’s one Big American Lie which is splashed in scarlet all over Twilight. Most of New Moon shows this do-it-to-death behavior, but especially chs. 4-10, in which we find Bella in the city late at night, high on fear, recklessly approaching four strange men; we find her exultantly and at least half-deliberately piling her dirt-bike, and ending up in the ER; we see her jumping, alone, off a high, rocky cliff into the pounding Pacific Ocean. Edward gone, Bella’s next addiction is Jacob (“ . . . I needed Jacob now, needed him like a drug [NM219].”). Too much of a good thing is never enough for Bella (or of a bad thing especially of a dangerous thing, something suicidal and exciting!).

[“I’ve never seen her so excited about reading before this . . . ”]

Suicide Will Fix It.

Bella has an epiphany after one of her motorcycle “accidents”: “ ‘Wow,’ I murmured. I was thrilled. This had to be it, the recipe for a hallucination [of the missing Edward] adrenaline plus danger plus stupidity (NM187-8).” And she follows this death-wish recipe with determination, until the day in Venice when she unexpectedly reacquires Edward at the precise moment of his own attempt at suicide. Not surprisingly, narcissistic, masochistic thrill-thrall Bella chooses for her fictional friends and models Cathy Earnshaw and Juliet Capulet (What, no Cleopatra? No Emma Bovary?). Many of our Twilight heroes Bella, Edward, Jacob, Carlisle, Rosalie are shown to us either contemplating suicide or actually attempting to kill themselves.

[“What’s all the fuss about?”]

The Horror of Being Human.

To some kids, ordinary is unacceptable; to some, normal is boring, even despicable. Bella ratchets this rebel teenage pose up to : human is loathsome, mortal intolerable. She thinks that because she’s just human, she’s not good enough to meet the Cullen Coven (T316), she’s unworthy to enter under their roof. Things merely human become for Bella, after her acquaintance with the Cullens mediocre, dull, useless. So, Bella proposes to herself a new goal : she must persuade some reluctant Cullen (maybe Alice) to bite her. She whines, “Against my better judgment, I was still human (E207).” But Bella is no quitter. “And I would do whatever it took to be a good person. A good vampire (E344).” (Some of Meyer’s prose would, I suspect, make even Ed Wood blush.) New werewolves quickly develop a similar preference. Good were (Anglo-Saxon for man) that’s negotiable; but by all means, be a good wolf. Leah, the yoga-aspirant/novice-werewolf, having trouble adjusting to the lycanthropic lifestyle, has this goal proposed to her by Jacob : Go all animal shed those human scruples and let your wolf-self take over that’s the secret to finding peace (BD313- 15). After Bella herself finally becomes a vampire, her “human memories” have for her what she calls “an aura of artificiality” about them (BD427). She calls turning vampire “the true beginning of my life (BD398).” All she really treasures from her former, fuzzy, pale, pathetic, insipid, and insignificant human life are her memories of Edward : “I would have to make sure those human memories were cemented into my infallible vampire mind (BD398).” Meyer’s anti-human bias, it must be admitted, feeds off the prejudice of too many of us Christians. Think of what you mean when you say things like only human, all too human, just human, to err is human : these phrases indicate that you’re considering only or at least mainly what’s wrong with us weakness, ignorance, sinfulness; you’re thinking of fallen man, using human as a synonym for sinner. (This exaggeration is due partly to Calvinist or Jansenist errors.) We need to remind ourselves that Redeemed man is something better than man in Original Innocence; man in the state of Grace is more like God than Adam and Eve were before they ate that Fruit. We need to inform the Bellas and Stephenies : Human is as good as it gets. God became human : Jesus is not superhuman, He’s man, He’s fully human. Immaculate Mary, His Mother, is 100% human. And the perfection and fulfillment of the human is the Divine, capital D. When we’re most human, we’re living God’s own Life, we’re holy. Grace makes us like God, not godlike, nor angelic, nor divine, small d nor any other seductive secular-humanist, New Age, or neopagan specious exaltation of humanity (which, because they are lies, are actually a degradation of humanity).

[“She doesn’t just vedge in front of the TV like she used to . . . ”]

The Curse of Marriage.

Bella worships Edward she’ll lie for him, she’ll kill for him, she’ll surrender her virginity, her life, her humanity (in fact, most of the drama in the story derives from her frenzied efforts to toss and trample those last three). But she draws the line at one of Edward’s requests : she will not marry him. Excuse me? The center of her universe, the drop-dead gorgeous object of all her romantic fantasies proposes marriage to Bella, and she refuses. Why? Because she had to live through the less-than-amicable divorce of her parents? And because marriage is dorky and old-fashioned, anyway, right? Am I the only one that finds this development a tad implausible? Frankly, I find a triangle composed of a high school girl who wants to be bit by a vampire, a 108 year old bloodsucker who sparkles in the sun, and a fun-loving, cute, Quileute, walrus-sized werewolf easier to swallow than Bella balking at Edward’s proposal. It seems though that for Bella there is a fate worse than death, a fate worse than eternal damnation (NM546-7) : being married to the one she loves. She must have him, but not as husband. Nothing is more horrible than marriage.

[“But she really loves Edward, even more than she loved Harry . . . ”]

No Sex Like Vampire Sex.

Like most Americans, Bella tends to identify romance, even just sex, with love (T195, T311, BD426). Human-on-human sex is okay, she guesses, for those who don’t know any better; but vampire-on-human sex is to die for (literally) (BD ch 5). And evidently this is true even when the perfect lover, Edward, on their wedding night, shreds the pillows with his fangs, chews the furniture (literally), and batters the body of his young bride black-and-blue. But vampire-on-vampire sex (BD420, 426), ah, that’s better yet, way better ”stronger.” Now, how does a merely human critic and a Christian one, at that deal with Bella’s values? How about : state the obvious? Romance isn’t love, Bella. Sex definitely isn’t love, Stephenie. There’s deeper error here, though more serious, too. Never seeing past surfaces angel voice, delicious scent, perfect body; persistently making decisions based on feelings romantic entanglement, erotic arousal, self-loathing, anger, despair; habitually acting on impulse, going with the flow, pursuing the obsession in other words, Bella’s life : this is guaranteed to lead, not to the happily-ever-after vampire love nest Meyer conjures (BD ch 39), but to real-world, this-world misery and self-destruction and in the end, probably to Hell, the real, next-world Hell.

[“All her friends are reading them, too . . . ”]

Werewolf Wife-Swapping.

Edward fears that he may be unable to give his beloved bride a baby (after all, Edward is dead) at least, a non-monster baby, an other than mother- killing baby. Edward this monomaniacal monument to monogamy, this possessive control freak, this full-on, one-woman vampire seriously suggests to Jacob (BD183), his werewolf rival, his inveterate (preter-) natural enemy (with whom his beloved, in Edward’s absence, has teased, flirted, and snuggled), that Jacob might do Edward the stud-service favor of making sure that Bella will not have to be denied the fulfillment of having a baby. Or puppy. Is this one of the elements of Meyer’s work that draws the praise of so many Evangelical and Catholic commentators who recommend these books as a happy part of today’s relevant, tolerant, inclusive, and nuanced chastity education for young Christians? (If you think I’m kidding, check the net.) Another of those elements, apparently, is the soft porn sprinkled like Splenda- Cyanide throughout the saga. Meyer displays the sighing, panting, touching, kissing, sniffing, stroking, and groping between Edward and Bella in her bed, night after night (while her father sleeps a few feet away), not, of course (we’re told) to titillate, certainly not, (we’re assured) to arouse, but to hold up for our admiration the icon of Edward the sexual brinksman ceaselessly testing his powers of restraint. There’s a model for our kids. [“Don’t forget, it’s make-believe . . .”]

Slaughtering Newborns.

In a story crowded with vampires and werewolves and all sorts of horrors, what is the most feared monster Ready? A newborn. That’s what they call the baby monsters, the uninitiated, outta-control neonate vampires. Though they’re strong and ferocious, it’s relatively easy for grown-up vampires to put an end to these new lives, which unfortunately often has to be done for the sake of the greater good. It’s not an easy decision, it’s not a course to be taken lightly, but sometimes a newborn’s life must be terminated for the grown-ups’ protection and to forestall a population explosion for the good of vampires everywhere. Is this starting to sound familiar? Then, there’s little Renesmee, the half-human vampire. Almost everybody wants her dead (everybody but Bella and Rosalie, the maternal maniac) : her father, the wise and sensitive Edward, wants to kill his daughter before she’s born; Jacob and the Quileutes plot “to cleanse the world of this abomination . . . ,” this “black, soulless demon (BD357-8).” Hey, we’re talking about an unborn little girl here, in a story written for little girls she’s half-vampire, yeah, but c’mon. Think we need this in a culture where we’re already

slaughtering preborns at the rate of about 4,000 a day? [“Don’t overreact it’s just fantasy . . . ”]

Mom Dum, Dad Double-Dum.

The broad-minded mom who responds to an alarm-ringing critic like me, “Whoa ?it’s only fantasy,” does not understand fantasy. What you fantasize, your body treats as real. That’s the point of fiction, that’s why we like stories : the medium is make- believe, the force, the feeling, the gut effects are for-real. And if delight, mom, can be real, so can damage. The sophisticated dad who, when warned of the unhealthy influence of Twilight, explains, “Her teacher recommended it” or, even more lamely, “Well, at least she’s reading” must ask himself, Can I trust this teacher, however well-intentioned, to choose fiction that will in fact be good for my daughter? Dad perhaps needs to consider, If every end-cap in Wal-Mart were bulging with de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom, and all her girlfriends were devouring it, and all the experts extolling it, would that make it good reading for my daughter?

Meyer’s Ministry of Truth.

In George Orwell’s 1984, the department of Big Brother’s government responsible for disseminating lies is called the Ministry of Truth. In Twilight, one must employ doublethink, the flipping of meanings, to begin to attempt to get hold of Meyer’s peculiar and perverse use of certain words. To the Cullens, biting, killing a human being (usually a suffering human being) is saving him, creating him anew, as a vampire; Edward refers to his own becoming a vampire as being born (T ch 16). Blasphemy to the rest of us, cursing God or hateful talk against God is, for Bella, growling at Edward (BD419); and for Edward, lying to Bella is “the very blackest kind of blasphemy (NM510).” Things unnatural, preternatural, or merely monstrous and extraordinary are constantly labeled supernatural. What other authors of vampire stories have typically called the undead, the living dead, Nosferatu (the plague-carriers), Meyer calls gods, angels, archangels, and especially immortals. The most savage and ferocious of Meyer’s monsters are, of course, newborns. The word coven (a group of witches, usually 13 of them) Meyer uses as a synonym for family. No Cullen in the bloody Cullen Family is related to any other bloodsucking Cullen by blood; you enter the Family when a Cullen kills you and turns you into a vampire. The concept of freedom is given a typical Big American Lie back spin : absolutely free, for Bella, means unthinking and utterly irresponsible (NM172). And for obsession, addiction, infatuation, and lust, one abused and overworked little word suffices : love. Bella says “Love is irrational . . . The more you loved someone, the less sense anything made (NM340).” At its deepest and most radical Jesus on the Cross it may seem folly, it may look insane; true love may indeed be beyond pedestrian human reason. But it is never irrational.

Monumental House of Cards.

When we first meet Bella, she loathes her dull life, dreads her boring prospects, and despises her klutzy, unattractive, oh-so-ordinary self. Then she meets Edward and there ensues first love, wild adventure, a lot of howling, bloodsucking, mayhem, and murder. When we leave her, at “The Happily Ever After (BD ch 39),” awash in a “tidal wave of happiness,” she has achieved more than she ever could have hoped for : perfect husband, perfect daughter (the perfection, of course, is all on Renesmee’s vampire side), and a blissful future that will never end Bella and her favorite people all safe, secure, and happy. Now all she wants, in her own words, is “ . . . some peace, some normality. I wanted Nessie in her own bed; I wanted the walls of my own little home around me (BD748).” Well, isn’t that the way a fairy tale is supposed to end? Yes, as long as the fairy tale teller hasn’t cheated along the way. And Meyer does cheat us. Her vampire romance is a fake and flimsy structure from cellar to dome, “a monumental house of cards,” like the one Emmett and Rosalie build under the stairs (BD516).

Vamp of Green Gables.

One of the Big American Lies that Meyer’s house of cards stands on is : You can have it both ways. According to my sources analysts Lang, Chesterton, Bettelheim, Frye, Campbell and, even better, analyst/storytellers MacDonald, Lewis, Tolkien, Shyamalan even in a fairy tale (especially in a fairy tale), you don’t get it all. There must be a trade-off for the hero, something lost for something gained. Most of the time, Bella manages to break the rules, take big risks, tempt death, and yet suffer minimal consequences; she gets to go wild and get away with it : as she puts it “Being reckless was paying off better than I’d thought (NM185).” Of course, Bella does lose her humanity, maybe her soul, too but Bella’s attitude about that stuff is Hey, no big good riddance (NM68). She’s learning to walk a new walk. She has a new belief system. Bella seems, up to this point, to have had no religion. Christianity is a sort of marginal curiosity to Bella she is shocked by Edward’s belief in Hell, his fear of damnation; she is amused, then annoyed, by his quaint, old-world idea (Edward died in 1918 at the age of 17) that people should be virgins till they marry. Bewildered by a large wooden cross hanging on the wall at the Cullens’, she is told by Edward, “You can laugh (T330)” : yeah, it’s ironic that cross, which would have terrified Dracula, is to the Cullens cute, a bit of nostalgia; Carlisle, you see, collects antiques. In Bella’s world, Christian morality is bizarre. Catholic beliefs are ludicrous, even contemptible : Jacob reflects on Leah’s mysterious pregnancy : “ . . . she couldn’t be pregnant not unless there was some really freaky religious immaculate crap going on (BD317).” Enter Edward : Bella sees the light, she gets religion. What religion? Vampirism. With Edward as god. When Edward, following his conscience, resists her demands that he turn her into a vampire, she shouts at him furiously, “This is about my soul, isn’t it? . . . I don’t care! You can have my soul. I don’t want it without you . . . ! (NM69) .” Finally, at the end of Meyer’s saga, Bella gets to be : nice suburban housewife; most powerful member of the Cullen Coven; rock-crushing supergirl; gentle, doting mother; Terror of the Volturi; most awesome babe and luckiest chick in Forks, Washington; budding, new neopagan (“I took mythology a lot more seriously since I’d become a vampire [BD525]);” well-beloved, even worshipped, wife; and preternatural parasite sucking the blood of the living (even, if she so chooses, “vegetarian” bloodsucker). In the end, she’s sweet Anne (with-an-E) Shirley and venomous, vicious Vampira, all wrapped up in one pretty, scary package having her blood and drinking it too forever.

This is cheating, logical and artistic cheating. Nobody gets it all (not in this world, anyway ?and no, not in a fairy tale, either) and least of all, somebody as chronically imprudent, as self-absorbed, as wrong-headed, and as self-destructive as Bella Swan.

Phony Fantasy.

There’s another kind of authorial cheating that must be held to Stephenie Meyer’s account. First, she trashes most of the canons of vampire lore and werewolf lore and offers us in their place her own complex secondary world with its own idiosyncratic canons. Second, this yields a specimen of what may prove to be a new genre : Postmodern-Postchristian-Neopagan Horror- Romance Adolescent Fantasy. All of which is fine, if it works. But it doesn’t work. The series is riddled with inconsistencies, contradictions, absurdities, and insults to common sense and I am not criticizing the fantasy elements, per se. It’s the false, the nonsensical, and the constant bursting of the bounds of plausibility within the realm of Meyer’s own subcreation, and according to her own rules (which she breaks or ignores at will) : that’s what cheats her readers. That’s what I can’t buy.

“Please, Bite Me,” Begs Little Red, of the Scandalized Wolf.

There are things, though, wrong with Twilight that are darker and much more twisted than any artistic quibbles. Here’s one : Robert Pattison, who plays Edward in the movies, was asked in a Rolling Stone interview, “Is it weird to have girls that are so young have this incredibly sexualized thing around you?” The handsome young actor responded, “It’s weird that you get 8-year-old girls coming up to you saying, ‘Can you just bite me? I want you to bite me.’ It is really strange how young the girls are, considering the book is based on the virtues of chastity, but I think it has the opposite effect on its readers . . .” Young Pattison sees the Emperor parading through the city, wearing nothing but a smile and a crown. He is puzzled, bothered, and almost does, but cannot quite, blurt the obvious. I can : The guy is naked. Twilight is not based on chastity. Twilight is based on lust perilous infatuation, bloodlust, and creepy, necrophilia-laced sexual lust. It’s lust masquerading in the darling, skimpy little outfit of a schoolgirl’s first love, a thing in our sex- besotted, porn-pummeled culture far more arousing than blatant obscenity. That the porn in these books is soft and not hardcore, titillating instead of graphic, romantic rather than raunchy, makes the novels more dangerous, not less, for those Meyer has targeted girls and young women. Where some gross triple-X trash would disgust and perhaps scare off curious young innocents, the powerful and protective, the handsome and gentlemanly, the glamorously suggestive Edward ambience lures them in.

All you beautiful Bellas, please listen : flirting with a sweet boy who turns into a giant, hairy, flesh-rending werewolf, a monster who’s mad with desire for you, is not cute; baring your throat under the flared nostrils of a powerful, thirsty vampire, a creature who’s mad with desire for you, is not love. It is reckless insanity. It is an invitation to death. (“But it’s only fanta?”) Oh, please. That it’s fantasy makes it more dangerous. If it were real, you’d scream and run. Telling yourself, It’s only fantasy gives you the illusion of safety and enables the lies and the twisted values of Twilight to penetrate your heart and take root in your life.

Do One, Tiny Bad Thing, and All These Great, Big Good Things Will Follow.

If there is one Big Human Lie at the root of all the evil in the world, it’s one of us knuckleheads saying : I’m God. And if there’s one Big American Lie at the foundation of our Culture of Death, it’s : The end justifies the means. Before he took the vow vegetarian, Edward the vigilante vampire only sucked to death rapists, brutes, and bad guys who really had it coming : that makes it okay (T343). It’s alright for Edward and Bella to be in bed together because : they are unconditionally and irrevocably in love; their relationship is solid, strong, stable, and mature; nothing bad can happen because Edward’s self-control is absolute; they cannot possibly live without each other; it can’t be wrong if it feels so right. (Try counting the errors in that batch; bet you miss a few.) Bella only lies to her parents to keep from hurting them. Jacob has to kill baby Renesmee because she is a serious threat to his people. The Volturi only slaughter crowds of unsuspecting tourists, torture indiscreet vampires, and decapitate the recalcitrant to keep the peace and to maintain law and order as Edward patiently explains to his outraged young wife : “[The Volturi are] only alleged to be heinous and evil by the criminals, Bella (BD580).” (A sentiment to warm the cockles of any fascist’s heart.) Meyer’s story implies, sometimes declares, that the lies told, the perversions indulged, the blood shed, the atrocities perpetrated by the Cullens are exonerated because Edward and company are good vampires they’re nice, they mean well, they act from the finest motives, always expecting to achieve results that will make the world a better place to live in. That kind of vacuous cant will gag anyone who knows one simple truth : There is no good end no matter how happy, blessed, big, and wonderful that can ever justify the smallest deliberate evil act.

Necrophilia (Ho Hum); Bestiality (Been There); Drinking Blood (Done That).

Three unspeakable practices, three unnatural acts that’s what they were a generation or two ago are now the stuff of children’s books. In Twilight, the necrophilia (Bella plus Edward) and the bestiality (Bella plus Jacob, almost) are implicit; the blood-drinking, right in your face. Pedophilia, child-molesting a really whacked strain of bestial-pedophilia, to boot is also implied (E174-6 and BD359+). True, Meyer does not show us anyone looking for a date in the graveyard, nor any man and beast checking into a motel. She does show us a vampire-human honeymoon, a human pregnant with a half-human half- vampire baby, and even, in one of the goriest and grossest scenes in the whole sanguinary saga, a vampire performing, with his fangs, a very messy c-section on his screaming, blood-vomiting, dying wife (BD346+ : Meyer calls Chapter 18 of Breaking Dawn “There Are No Words for This.” As it happens, I’ve got a few sick, horrific, sad, repulsive, unholy, foul, unnatural, evil . . . ). Meyer does show us giant werewolves imprinting with human baby girls Quil with two year old Claire (E174+) and Jacob with little Renesmee, within minutes of her birth (BD359+). Imprinting is a mysterious permanent personal link, irresistible and unbreakable, experienced by a werewolf at the first sight of his prospective mate : it’s many things, but ultimately sexual. Even Bella, brainwashed toddler of tolerance that she is, trying her hardest not to be critical, is horrified (E175-6). Jacob, disappointed and indignant at her incorrect attitude to his werewolf friend’s sexual designs upon the two year old Claire, accuses her, “You’re making judgments . . . I can see it on your face.” Bella mutters an apology.

The Not-So-Slow Boiling Christian Frog.

If even just a few of the above judgments about Twilight are valid, then how can the stories be not only runaway bestsellers and smashes at the box office, but very popular with practicing Catholic families, favorites among respected Christian critics, huge hits with home-schoolers? One of the broadest effects of these vampire romances is the further desensitization of our already pretty severely seared consciences. “Decent” Christians, “devout” Catholics are not only not shocked, not outraged by Twilight, but they themselves enjoy the novels, recommend them to friends, buy them for their children. Art that would have made our grandparents puke is today promoted by our pastors, youth ministers, and Sunday school teachers.

Is there something wrong with us?

Yes, there is something wrong with us something life-threatening. We are beyond decadent, we’re past jaded. Some time ago we went zooming off the edge of that slippery slope and are now in free fall. And we still have not noticed. Why? It’s like the remark made by the old lady standing in the shadow of the gallows : “People get used to anything get used to hanging, if you hang long enough.”

Consider Charlie. Bella’s dad is a regular kind of guy small town cop, easy-going, wants his daughter to be happy, likes his TV, football, and beer. At the end of Breaking Dawn, his daughter is already a vampire; Charlie’s granddaughter is a three month old prodigy, smarter and stronger than most three-year-olds, with a fierce thirst for human blood; Charlie has just seen Jacob phase into a werewolf. Charlie is beginning, slowly, to put the pieces together, and he’s finding it very disturbing. He drops in at the Cullens. This is, for me, the most terrifying passage that Stephenie Meyer has written :

Charlie nodded and . . . glanced past me into the house; his eyes were a little wild for a minute as he stared around the big bright room. Everyone was still there, besides Jacob, who I could hear raiding the refrigerator in the kitchen; Alice was lounging on the bottom step of the staircase with Jasper’s head in her lap; Carlisle had his head bent over a fat book in his lap; Esme was humming to herself, sketching on a notepad, while Rosalie and Emmett laid out the foundation for a monumental house of cards under the stairs; Edward had drifted to his piano and was playing very softly to himself. There was no evidence that the day was coming to a close, that it might be time to eat or shift activities in preparation for the evening. Something intangible had changed in the atmosphere. The Cullens weren’t trying as hard as they usually did the human charade had slipped ever so slightly, enough for Charlie to feel the difference. He shuddered, shook his head, and sighed. “See you tomorrow, Bella.” He frowned and then added, “I mean, it’s not like you don’t look . . . good. I’ll get used to it.” “Thanks, Dad (BD516-7).” Comfort-loving, media-brainwashed, confrontation-avoiding Charlie is going to get used to he plans to get used to his only daughter marrying a vampire, hanging out with werewolves, and becoming a monster herself. But don’t judge poor Charlie. Don’t you dare get judgmental. Remember : Twilight is fantasy. Charlie is only a creature drawn from Stephenie Meyer’s fertile imagination, right? Besides, everybody knows, there are no such things as vampires and werewolves. Not in the real world. Right? Uh, as a matter of fact, wrong there are such things. You can check out their ads on the net and in the personals of some newspapers newspapers readily available in West Hollywood, Greenwich Village, New Orleans, Las Vegas, San Francisco, and probably before long, in Chicken Gristle, Kentucky. You can also read their true, sad stories in case history texts published by practitioners of the American Psychiatric Association. These sick people won’t remind you much of the Cullens or the Quileutes. They’re real and they’re really ill, emotionally and mentally. But their numbers are growing, thanks partly to Stephenie Meyer and her imitators (whose numbers are also growing). You need not have too much fear (not yet anyway) of the werewolves who are, or soon will be, psychiatric patients; no immediate need (not, I think, in most locales) to walk in dread of the want-ad vampires who hook up with “willing” victims out of some psychological compulsion they think is a physiological thirst. Don’t fear them. But there is somebody else to fear.

Almost Everyone Is a Zombie Now.

I’ll show you whom you ought to fear the one who is a real monster, the one who is a true killer a monster that is a soul-destroying, not a flesh-eating, zombie.

About a third of the way through the Twilight saga, desponding, Edwardless Bella goes to the show to see a zombie movie with her friend Jessica. To avoid the romantic scene that begins the movie, such scenes now too painful for her broken heart to endure, Bella rushes out to the snack bar. She waits ten minutes, then approaches the theater doors to check what’s happening inside in the dark; she listens:

I could hear horrified screams blaring from the speakers, so I knew I’d waited long enough.

“You missed everything,” Jessica murmured when I slid back into my seat. “Almost everyone is a zombie now (NM105). ”

Bella then has a flash of insight, a glimpse of herself as she really is.

The rest of the movie was comprised of gruesome zombie attacks and endless screaming from the handful of people left alive, their numbers dwindling quickly. I would have thought there was nothing in that to disturb me. But I felt un- easy, and I wasn’t sure why at first.

It wasn’t until almost the very end, as I watched a haggard zombie shambling after the last shrieking survivor, that I realized what the problem was. The scene kept cutting between the horrified face of the heroine, and the dead , emotionless face of her pursuer, back and forth as it closed the distance. And I realized which one resembled me the most (NM106).

Sitting in the darkened theater, bathed in flickering zombie carnage, Bella’s jolting encounter with truth is like something out of Flannery O’Connor grotesquerie. Bella sees she’s the zombie, the one that’s dead; if she’s the victim being devoured, she’s also the monster doing the devouring. O’Connor described such a storyteller’s stroke of drama, and trauma the heart of every one of her own stories as the offer of Grace. In that moment, God offers light and strength to a person in crisis, someone teetering on the brink. What follows, unhappily and usually in O’Connor’s stories, is that the person either refuses the Grace or is too blind to recognize it. Bella responds to her shocking moment of insight like Mr. Shiflet in “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” : she blows it off. She sees, but misconstrues, the message of truth she reads Without God, you’re dead. as Without Edward, you’re dead. Then she dismisses the flash of truth, forgets it, and continues her progress down the path of despair and self- destruction. She has a stunning glimpse of reality, then immediately rushes back to her friends, the monsters, of whom she has no idea that she should be afraid. Sadly, poor little Bella also seems to have no clue that her deadliest and most dangerous enemy is poor little Bella.

Real Life Is Death to This World.

The vampire that’s going to suck me dry is me. The werewolf that’s going to rip your heart out is you. We live in a world that loves death. No, not consciously. We say, and we think it’s true, that we love life just like our parents doubtless said and thought in the Garden. That bright and beautiful and shiny red apple offered on the cover of Twilight (and on tee-shirts over the legend : Forbidden Fruit Is the Most Delicious) is the perfect emblem for Meyer’s saga. Her Edward is bright and beautiful and shiny, too (well, sparkly); her Jacob is studly and charming, wild and full of fun; what girl wouldn’t be attracted to either one or the other or, like Bella, to both? Little girls and young women fall for Jake and Edward for good and healthy and normal reasons : Edward and Jacob are manly, self-sacrificing, generous, brave, faithful, sensitive, more concerned with Bella’s happiness than with their own. They are, in these virtues, what all men are supposed to be, but, in fact, are not. That’s the sneaky, insidious part : Edward and Jacob are the pretty that makes the poison palatable.

Don’t Be Charlie.

Once upon a time, in the most beautiful and happiest Garden in the whole world, our mother gazed with longing and curiosity at the Fruit, beautiful and deadly, that God had forbidden her and our father to eat. Our mother saw that the Forbidden Fruit was good for food (for animals, that is, other than herself and her man), and she was right; she saw that the Fruit was pleasing to the eye, and so it was; she saw that it was desirable for gaining knowledge, and she was wrong. She was dead wrong.

The main reason that a critique in moral and spiritual terms, like this one, of something as unhealthy and corrupting as Twilight (this goes for Harry Potter, too) is needed is that we are dead dead inside, or at least approaching death in our Christian sensibilities. For too many of us, our critical faculties, if not yet six-feet-under, are at least deadened, our consciences comatose. If you and I are not deliberately and vigorously resisting its pull, death, the second death (Rev 20:14), is right now working its will with us. If you and I think we can coast after Christ, we’re already the undead, or are at least zombies-in-the-making. I am the monster I need to fear. You are the zombie that’s eating your soul.

Don’t be Charlie. You cannot help it that you live in the Culture of Death. To some extent, you cannot even help getting used to it (how can we be shocked, how can we stay outraged, when we are daily and hourly being bombarded with horrors). American lies, errors, and downside-up values are not going away, but don’t resign yourself to the status quo, don’t just passively go along. If we’re Christian, we must not accept the Big American Lies. For the love of God, and for love of your family, do not, because of comfort or convenience or cowardice or sloth, embrace these lies. Swim against the stream, buck the trends, make waves, rock the boat. Fight the zombie in you. Like the werewolf said, Don’t hang out with vampires. Don’t make friends with Meyer’s monsters, don’t get comfortable with Rowling’s sorcerers and witches they’ll mess up the way you see the world. See everything in the light of the Holy Spirit, learn to look at this dark place through Jesus’ eyes. Also, do not presume to judge Rowling or Meyer or any of their imitators; leave that to Jesus. Pray for them, love them. But judge their behavior, judge the product, judge the fruits (Don’t you know we’re going to judge angels?). Assess their writings according to Jesus’ standards, and condemn the evil there that is causing little ones to fall. If you love your children, do not allow the schlockmeisters of death to mess with your sons’ minds, to manipulate your daughters’ hearts.

Christeyes Coda – Little Girl for Breakfast

The Pevensie children have just been saved from the attack of a wild bear by Trumpkin’s arrow, and Susan fears the animal may have been a Narnian talking bear that has reverted to savagery. Susan, upset, says :

“I was so afraid it might be, you know one of our kind of bears, a talking bear.” She hated killing things.

“That’s the trouble of it,” said Trumpkin, “when most of the beasts have gone enemy and gone dumb, but there are still some of the other kind left. You never know, and you daren’t wait to see.”

“Poor old Bruin,” said Susan. “You don’t think he was?”

“Not he,” said the dwarf. “I saw the face and I heard the snarl. He only wanted Little Girl for his breakfast . . . ”

. . . Lucy shuddered and nodded. When they had sat down, she said : “Such a horrible idea has come into my head, Su.”

“What’s that?”

“Wouldn’t it be dreadful if someday in our own world, at home, men started going wild inside, like the animals here, and still looked like men, so that you’d never know which were which?”

C. S. Lewis’s Prince Caspian, ch 9 – “What Lucy Saw”